Special and/or Limited Editions have always held an unusual place in Intel’s lineup. Being neither fish nor fowl nor good red meant that each time Intel did release one you never knew in advance what it would be/do/offer over the standard models. In fact, at one point in history they were meant to mark… well… special occasions. Instead of being released seemingly every generation. Take the “Pentium 20th Anniversary Edition” G3258 CPU for example. It was not the fastest, not the most expensive (MSRP of only 72 USD!), nor even the most powerful CPU at the time (as it was only a 53 watt TDP, dual core CPU). Instead, it was special because it came multiplier unlocked and just plain fun to go down the nostalgia route and celebrate 20 successful years of the Pentium brand. The same was not true of the Intel 40th Anniversary 8086K. It too was special, but it was both the most expensive, and the rip-snortin’ fastest Intel mainstream CPU available at that time. So while we were a big fan of the former… the latter? No so much.

In between those two disparate examples, some people argued that the Core i9 was supposed to be each generations Special Edition – as it upturned the whole entry/main/high-end (core i3/5/7) nomenclature Intel had used up until then. Others argue that the ‘X’ branded models were all Special Editions as they were the EXtreme Editions. We think neither is true, but Intel did undermine their rather consistent nomenclature by randomly adding in Special/Limited/etc. editions with widely varying abilities (and price points).

In either case the last official consumer desktop Special Edition CPU was the Intel 9th Generation Core i9 9900KS. It came with a with a mere $25 boost in MSRP($513 vs $489 for the 9900K) and offered buyers an equally anemic boost in performance. It… did not sell well. That MSRP was quickly ignored by most retailers and the real-world average price was high enough to make AMD’s Ryzen 9 price look good in comparison. Sales were (rumored to be) so less than optimal that they skipped a mainstream Special Edition for the 10th (though they did release a ‘KA’ version of the Core i9-10900 CPU… but it was just a standard 10900K in a “special edition” Avengers branded box). Same for the 11th generation where Intel once again did not offer a desktop Special Edition (though once again to be fair a mobile Special Edition in the form of a Core i7-11375H was released).

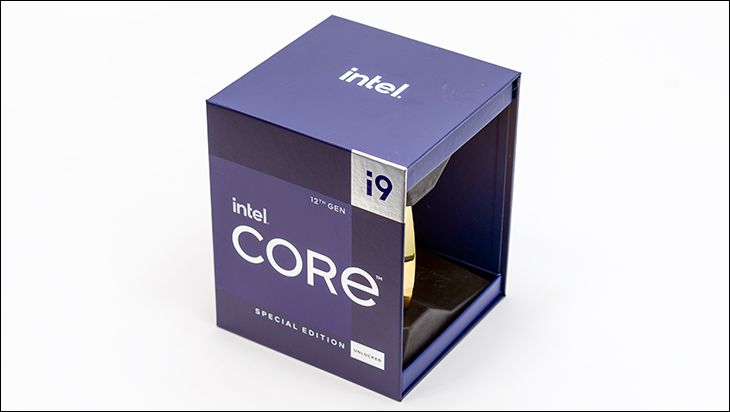

For the 12th Generation it appears that Intel has finally (hopefully) settled in on a consistent naming scheme for Special Editions. Special Editions are to take their cues from the 8086K and be the fastest, hottest, most expensive consumer desktop processor Intel can make in a given generation. In this generation that means a 16 core beast that can hit 5.5Ghz on one active p-core, 4.0Ghz on an e-core, have all eight p-cores ticking along at 5.2GHz, and guarantee that (unless you are using a potato for a cooler) will be at least running at 3.4Ghz / 2.5Ghz (p/e-cores). Out of the box with zero tweaking necessary.

To do that Intel did not reinvent the wheel (again). Instead, they have increased the testing process and procedures all Core i-series chips coming off the Intel 7 fab line go through. This is where a bit of terminology requires explaining/defining as not everyone knows what it means when someone says ‘binning’ and/or ‘golden core’. The binning process basically means that all fresh out the oven Core I-series cores start out as potential Core i9s and are tested to that standard. Those that past the first round of sorting are separated from the failures – with the failures then becoming potential Core i7s and tested to that standard. Those that fail standard are tested at Core i5 standards. Those that fail become potential i3s… and down and down the rejects go. This testing to see how good a given CPU is, is called ‘binning’… as they were originally sorted into actual bins for further sub-testing and/or into the garbage bin if they were utter trash and could not even pass Celeron standards.

When the 12gen was first released the first round of binning was “easy”. All a 12th Gen. Core I processor had to be capable of doing was being stable at 5.0GHz on all 8 P-Cores and 2.5GHz on all 8 E-Cores. Obviously… all at the same time, at ‘stock’ voltages, and only consuming 125 watts of power. If they passed, then they also had to be stable with one p-core active at 5.2Ghz and one active e-core at 3.9Ghz (with a relaxed 241 watts allowed). This is why there was (and to a lesser extent still is) such variances in overclocking potential in those early release Core i9-12900K CPUs. Some could barely do better than stock. Others tapped out at 5.3GHz, and a special few could do 5.5Ghz or even higher. Those in the last group were / are called ‘Golden’ chips and were the best of the best of any given batch. Why ‘golden’ and not ‘platinum’ or ‘diamond’ or ‘rhodium’? In the immortal words of The Critical Drinker “Don’t Knoooow”. Most, including ourselves, believe the slang stems from Gold/Silver/Bronze awards with the three tiers equating to how good an overclocker a given CPU was.

In any case. That flow was how Intel did it originally with the 12 generation. With the release of a Special Edition Intel has increased the first test standards. Now all are tested to see if they can handle 5.2Ghz all core boost on the P-cores, single core p-core of 5.5Ghz, and 4.0Ghz on an e-core. All with just the same stock amount of voltage being applied. Though to be fair Intel does allow it to consume 150 watts instead of 125 watts but only the same 241 watt burst as the 12900K test. While that does not sound all that much more stringent… a rumored low single digit percentage of processors can pass this test.

Since all are tested against this more demanding standard that is a lot of failures and time ‘wasted’. Time is money when it comes to CPU manufacturing. Anything that slows down a production line… well… the cost must be recouped somehow, somewhere and from someone. Thus the $150 increase in the Special Edition’s asking price – as it is covering the increased time sunk into every Core I processor… not just the ones that pass the first round. Hopefully, this Special Edition sells better than the last and Intel can ‘adjust’ their price-tiers to be more in line with the 9900KS rather than the 8086K.

When talking about overclocking and the Intel 12900KS a few key words do spring to mind. The foremost of which is smooth, followed by easy and forgiving. That is because the 12900KS is pretty much easy mode for overclocking compared to the rest of 12th generation Core I series (which they themselves are not difficult processors to overclock). With that said, for those who have worked with a lot of Intel 12th Gen Core i9s recently the differences will not be massive. If you were lucky enough to happen upon a ‘golden’ or even just close to golden CPU that loved to be overclocked you know how easy things can go. Just imagine that experience… but even better.

For those who have not been as lucky, the differences will be a bit bigger… but make no mistake the differences are not going to be “Bigly Yuge”. You will land within the same upper boundaries as what the best of the 12900K could do… you just should be able to routinely do it. That is to say, you should be able to easily get 5.3GHz/4.0GHz (p/e) “all core” overclock. Most should be able to hit 5.4/4.1. Many should, assuming good enough cooling is used, do 5.5/4.2 – or some combination of P and E core overclocking at reasonable(ish) voltages. Ours easily blew past the former options and did the latter with very little effort. So much so we could have dialed things up to 5.6 and/or 4.3… or possibly 4.4 on the e-cores. Since voltages were starting to hit the point of diminishing returns we dialed back to 5.5+4.2 and called it good. At this level of overclocking it was running slightly cooler (and quieter) than the Core i9-12900K we previously tested… at 5.3/4.2. That 12900K CPU sample was upper average for the 12th Gen but it outclassed that much by this new edition. Color us moderately impressed.

The Integrated Memory Controller was also extremely good, and phrases such as ‘best we have seen from Intel’ did randomly crop up when playing with this particular CPU. So much so this is the very first time that we wish we had even faster DDR5 RAM to use. That however would have skewed the results in our charts further. As such we dialed things back to the exact same settings used with the Core i9-12900K (and lower). We know we were not pushing that IMC but that is fine. There is a point of diminishing returns right now with DDR5 overclockable RAM… as they are bloody expensive.